Category: Publications

-

The Armenian Genocide in Feature Films

(armenianweekly.com) With the recent release on DVD of the major motion picture “The Promise,” greater numbers of people will be able to gain insights into aspects of the Armenian Genocide. The film, starring Christian Bale, Oscar Isaac, and Charlotte Le Bon, was directed by acclaimed filmmaker Terry George, who had been involved in the production…

-

Canadian Museum for Human Rights Produces Film about Armenian Genocide

(horizonweekly.com) TORONTO, Ontario—In partnership with the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR), the Armenian National Committee of Canada co-organized the premiere of the museum’s new film about the Armenian Genocide, “Acts of Conscience: Armin T. Wegner and the Armenian Genocide” on October 13th, 2016. The event took place at the Armenian Youth Centre of Toronto…

-

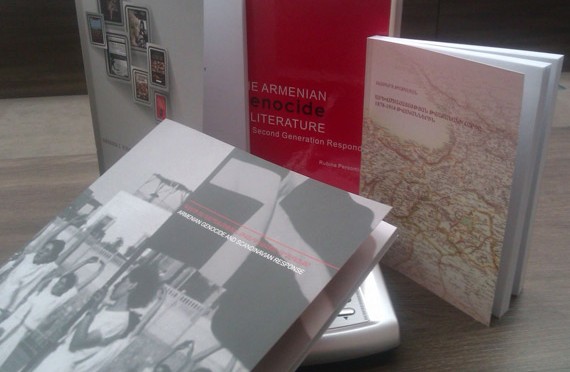

Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute presents four new volumes

(tert.am) The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute has published the new monograph of Armen Kirakossian “The Armenian Genocide in Contemporary American Encyclopedias”. The edition was presented in English. In this publication Dr. Arman Kirakossian studied and analyzed nearly forty specialized and thematic encyclopedias (Encyclopedia of War Crimes and Genocide, Encyclopedia of Genocide, etc.), dictionaries (Dictionary of Genocide,…

-

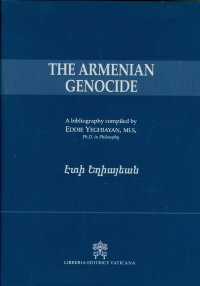

The Most Up-To-Date Bibliography on the Armenian Genocide. Book Review by: Dr. Garabet K. Moumdjian

(horizonweekly.ca) Eddie Yeghiayan’s recently published collection of works dealing with the Armenian Genocide surpasses all previous bibliographies on the subject in both scope and ambition. Encompassing various forms of media in a multitude of languages and stretching at over a thousand pages, it is massive, yet meticulously catalogued and comprehensive volume. The bibliography will aid…

-

Armenian Museum of Fresno Releases Eye-Witness Accounts of Genocide in New Book

(asbarez.com) FRESNO—The Armenian Museum of Fresno is proud to release The Cry of the Tormented, a book comprised of more than 300 letters written by Armenians during 1915-1918 who were facing atrocities, starvation, deportation, murder, and annihilation. These letters were written to relatives and friends across the world, including those who settled in Fresno and…

-

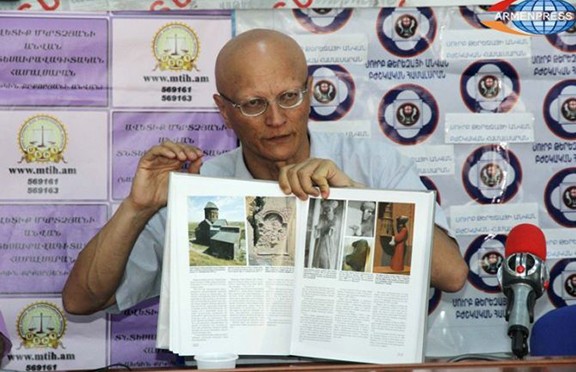

Book “Genocide after Genocide” Aims to Fight Cultural Genocide in Turkey

YEREVAN (ARMENPRESS)—The Foundation for Research on Armenian Architecture has published a new book, “Genocide after Genocide”, which it hopes will contribute to the struggle against cultural genocide in Turkey. Samvel Karapetyan, head of the Foundation for Research on Armenian Architecture, described the book as a weapon which can be used to stop the destruction of…

-

Remembering the Armenian Genocide 1915

Remembering the Armenian Genocide 1915 By Canon Patrick Thomas Publication Date April 2015 Publisher: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst (horizonweekly.ca) 2015 is the centenary of that Armenian Genocide. In this moving and powerful account of the suffering undergone by Armenians, Patrick Thomas draws on eye-witness material from a wide variety of sources. He shows why it…

-

Resolution with Justice: Theriault Discusses Armenian Genocide Reparations Report

Special for the Armenian Weekly by Rupen Janbazian While recognition of the Armenian Genocide by the government of Turkey has been a priority for Armenian communities around the world, the notion of legal consequences that can emerge after recognition has generally been unaddressed or ignored. Certainly, the question of reparations for losses suffered both by…

-

Bedros: new book about the Armenian Genocide

(Horizon Weekly) Bedros, by Irene Vosbikian. Bedros is the inspirational saga of a man who, his father butchered before his eyes, survives the Armenian Genocide – the first genocide of the 20th century. It is a true story of hope, perseverance and bravery. Bedros is an inspiration to the descendants of all the persecuted immigrants…

-

‘Genocide Studies International’ Examines the Armenian Genocide, Geopolitics, and Denial

(armenianweekly.com) The International Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (A Division of the Zoryan Institute) recently announced the release of “Genocide Studies International” (GSI), volume 8, number 2, Fall 2014. This peer-reviewed journal, edited by the scholarly team of Maureen Hiebert, Herbert Hirsch, Roger W. Smith, and Henry Theriault, is interdisciplinary and comparative in…