Category: Other

-

The Armenian Genocide in Feature Films

(armenianweekly.com) With the recent release on DVD of the major motion picture “The Promise,” greater numbers of people will be able to gain insights into aspects of the Armenian Genocide. The film, starring Christian Bale, Oscar Isaac, and Charlotte Le Bon, was directed by acclaimed filmmaker Terry George, who had been involved in the production…

-

Canadian Museum for Human Rights Produces Film about Armenian Genocide

(horizonweekly.com) TORONTO, Ontario—In partnership with the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR), the Armenian National Committee of Canada co-organized the premiere of the museum’s new film about the Armenian Genocide, “Acts of Conscience: Armin T. Wegner and the Armenian Genocide” on October 13th, 2016. The event took place at the Armenian Youth Centre of Toronto…

-

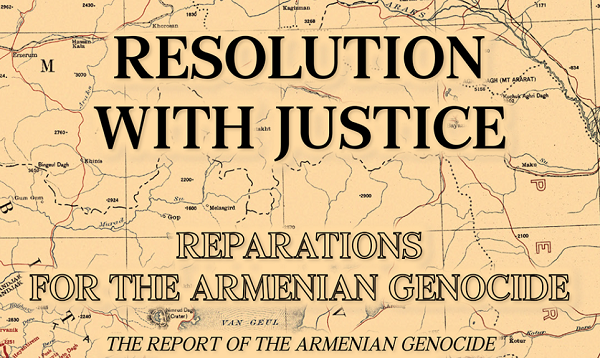

Resolution with Justice: Theriault Discusses Armenian Genocide Reparations Report

Special for the Armenian Weekly by Rupen Janbazian While recognition of the Armenian Genocide by the government of Turkey has been a priority for Armenian communities around the world, the notion of legal consequences that can emerge after recognition has generally been unaddressed or ignored. Certainly, the question of reparations for losses suffered both by…

-

‘Genocide Studies International’ Examines the Armenian Genocide, Geopolitics, and Denial

(armenianweekly.com) The International Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (A Division of the Zoryan Institute) recently announced the release of “Genocide Studies International” (GSI), volume 8, number 2, Fall 2014. This peer-reviewed journal, edited by the scholarly team of Maureen Hiebert, Herbert Hirsch, Roger W. Smith, and Henry Theriault, is interdisciplinary and comparative in…

-

Armenian Genocide Reparations Study Group Publishes Final Report

YEREVAN—The Armenian Genocide Reparations Study Group (AGRSG) has just completed its final report, “Resolution with Justice – Reparations for the Armenian Genocide.” The report offers an unprecedented comprehensive analysis of the legal, historical, political, and ethical dimensions of the question of reparations for the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1923, including specific recommendations for the components of…

-

Genocide Encyclopedias and the Armenian Genocide

by Alan Whitehorn* Special for the Armenian Weekly The two key human rights concepts of “crimes against humanity” and “genocide” have their roots in the response to the Young Turk mass deportations and massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Following the April 24, 1915 mass arrests of hundreds of Armenian…

-

ABC 7.30 airs feature on Turkish Gallipoli ban threat against Australians

(armenia.com.au, SYDNEY) – Australia’s national broadcaster, the ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), aired a powerful feature on Australia’s connection to the Armenian Genocide, and the recent threats made by the Turkey’s Foreign Ministry to ban Australian politicians from attending ANZAC Day centenary commemorations in Gallipoli. The feature was part of the prime-time “7.30” program (WATCH THE…

-

Turkey’s “race codes” and the Ottoman legacy

VICKEN CHETERIAN 20 August 2013 The revelation that modern Turkey continues secretly to classify its citizens according to religious criteria reflects the weight of the Ottoman past. It also has implications for those in the middle east seeking a state based on equality before law, says Vicken Cheterian. Only days before the verdict in the latest…

-

ACF sponsors publication of volume on Armenia and post-WWII Soviet-Turkish relations

The Armenian Cause Foundation recently sponsored the publication of the book by the National Archives of Armenia. The book details an insufficiently studied episode of the Armenian Question, namely the demand by the Soviet government that Turkey return Kars to Armenia in 1945 as a pre-condition for signing a new treaty of friendship between USSR…